Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...-

Call us on (973) 810-2976

- My Account

- Gift Certificates

- Items / $0.00

All prices are in All prices are in USD

Categories

- Home

- Documents/Ephemera

- Rare - Libby Prison Museum Advertising Card, 1889

- Home

- Photographs

- Rare - Libby Prison Museum Advertising Card, 1889

- Home

- Miscellaneous 19th Century

- Rare - Libby Prison Museum Advertising Card, 1889

- Home

- Identified Artifacts

- Rare - Libby Prison Museum Advertising Card, 1889

- Home

- Non-excavated Artifacts

- Rare - Libby Prison Museum Advertising Card, 1889

- Home

- Personal Items

- Rare - Libby Prison Museum Advertising Card, 1889

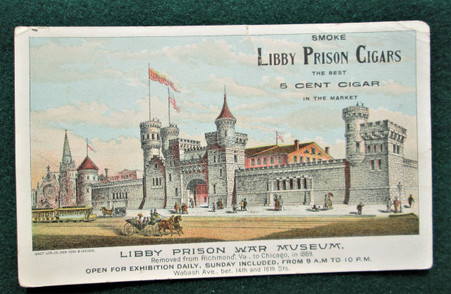

Rare - Libby Prison Museum Advertising Card, 1889

Product Description

This is another unique item being offered, it is an original advertising card of the famous Libby Prison. The card measures 5 1/2” by 3 ¼” and is marked on the bottom with “LibbyPrisonWarMuseum”. On the top is “Smoke Libby Prison Cigars / the Best/ 5 Cent Cigar / in the Market”. In 1845 there arose in that city near the James River a sturdy and nondescript oblong brick box, three stories high. It served for a time as a tobacco warehouse; in 1861 a large sign proclaimed it the home of Libby and Son, Ship Chandlers and Grocers. War plucked the building, as it did many individuals, from obscurity. Greatness was thrust upon it--if only great infamy--when the Confederate government appropriated it as a prison for captured Union officers. Whether it or its rural counterpart at Andersonville became more notorious in the North would be hard to say. Prisoners held at Libby --over the course of the war there were forty-five thousand of them--complained vociferously during the conflict and afterward of hunger, brutal treatment and theft by their captors, winter cold and damp and close confinement in overcrowded quarters.

After the war the name of Libby remained instantly recognizable. When a group of Chicagoans visited Richmond in the late 1880s, however, they found the building lapsed into its antebellum shadows and more than its antebellum seediness. “Beside it,” a reporter observed, “the stockyards are a bower of roses.” The company in possession manufactured fertilizer from fish and animal carcasses. Yet underneath the reek and refuse, the traces of the prison stood intact. “The heavy floors,” though “... thickly covered with dirt,” retained the checker and backgammon boards carved by desperately bored prisoners. The sturdy wooden posts were “thick with soldiers’ names cut deep into the wood.” They struck the visitors as capable of supporting a much more lucrative trade. The Chicagoans arranged to buy the structure. They planned to disassemble it, take it home, and rebuild it as a tourist attraction.

No local sentiment anchored Libby Prison in place. The objections to relocating it came from elsewhere. Northern veterans who had been imprisoned in Libby vehemently objected to having the scenes of their sufferings made into “a 10-cent show” for “the benefit of a clique of vulgar speculators....” It would “collect dimes and dollars as a ghastly circus exhibition to fill the pockets of sharp, unprincipled ... men that have conceived the selfish and despicable idea of violating the sanctity of the soldiers’ sufferings and to many the very spot of their deaths.” For weeks opponents besieged the mayor of Richmond and the governor of Virginia with demands that the scheme be stopped. Outgunned and outmaneuvered, however, they were soon driven off.

On May 6 a train carrying part of the dismantled prison broke an axle and jumped the tracks near Springdale, Kentucky. There were no human casualties, but the local population turned out in force to scavenge souvenirs from the debris. Most of the loss would be recovered and eventually it would end up as part of the Charles F. Gunther collection. He was a candy manufacturer and an avid Civil War collector. With Libby, he found the perfect specimen--Libby was to be made a museum for his Civil War memorabilia. Gunther spoke to the newspapers and minimized the damage done in the accident, picked up the pieces (or those that remained), and got the venture back on track. He opened Libby to the public in Chicago on September 20, 1889.

The museum was an immediate success and one of the nation’s most talked-about attractions. A decade after opening his museum, Charles Gunther decided he needed the prime lot it occupied for his Chicago Coliseum. So Libby was again torn down, the victim of commercial zeal. Made novel and colorful to attract business, it became expendable once the novelty had worn off, as enticing and as disposable as the wrappers in which its owner packaged the candies that were his main line of work. Yet as a gesture to the past, Gunther retained Libby’s facade within a wall of the far larger building that replaced it. In 1920 he sold his collection to the Chicago Historical Society, and it became the cornerstone of that institution’s great Civil War holdings. When the Coliseum was eventually torn down in 1982, Libby’s much-traveled facade made one final journey, across town to the historical society, to come to rest amid the memorabilia it had once housed and in the proper hands at last. One wonders how it would have fared if it stayed in Richmond. This rare image is absolutely beautiful…it is very clear and is in very nice condition except for a tiny tear at the top. I also have a war time stereocard of the prison in my photographs category. (FREE SHIPPING)